|

This article originally appeared in the June 2022 issue of Woods-N-Water News

By Drew YoungeDyke The Recovering America’s Wildlife Act is poised to pass Congress after being advanced by committees in both the U.S. Senate and the U.S. House of Representatives, with over 30 bipartisan cosponsors in the Senate and over 170 in the House. This legislation – which would provide $1.39 billion annually in wildlife restoration funding - would be the biggest conservation bill perhaps since 1937’s Pittman-Robertson Act that directed excise taxes on hunting and shooting equipment to wildlife restoration. It’s sorely needed right now as up to one-third of fish and wildlife species in America are at increased risk for extirpation or extinction, as maintained by each state’s list of Species of Greatest Conservation Need. The Recovering America’s Wildlife Act was co-sponsored in the House by Michigan Rep. Debbie Dingell (D) and Nebraska Rep. John Fortenberry (R), and in the Senate by New Mexico Sen. Martin Heinrich (D) and Missouri Sen. Roy Blunt (R). It has been introduced each term since 2016, but for the first time ever, it has now passed essential committees in each chamber and is ready for a floor vote in each. And it may not get another chance. If the Pittman-Robertson Act was so successful, though, why is a bill like the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act needed now? Some brief conservation history will help to understand. For the first couple hundred years of settler colonial history in the United States, the conservation of fish and wildlife was not a priority. Abundant fish and wildlife populations conserved by Indigenous generations for millennia flourished, but as their lands were taken the wildlife was exploited commercially and reduced to alarmingly low numbers by the early 20th century. Conservationists responded to the wildlife crisis by establishing game laws, conservation departments and commissions, license fees and, finally, in 1937, dedicated funding to restore wildlife populations through the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act - known as the Pittman-Robertson Act – to direct the excise tax on firearms and equipment to state conservation departments for wildlife restoration. In 1950, Congress passed the Dingell-Johnson Act to apply the same concept to fishing and boating equipment to fund fish conservation. As most hunters and anglers learn in hunter’s safety courses, this funding allowed state conservation departments to hire professional fish and wildlife biologists and fund the restoration of fish and wildlife. Most of that effort was directed at iconic game species like white-tailed deer and wild turkeys. Through a system employing professional biologists to make recommendations on actions like license quotas, bag limits, hunting and fishing regulations, and reintroductions and stocking, fish and game populations thrived, and most still do today. However, many smaller non-game species have not thrived. Their pressures are different. For instance, overhunting was not the cause of decline for monarch butterflies, so game regulations can’t do much to restore them. The pressures on the primarily one-third of American fish and wildlife species on the state Species of Greatest Conservation Need lists are the pressures of American society itself: things like habitat loss, wetland conversion, the effects of pesticides, or invasive species. And funding for wildlife agencies to mitigate these pressures to keep these species off the endangered lists has never been adequate, and certainly not on par with the hunter- and angler- funded conservation efforts for fish and game species. In 1973, Congress passed the Endangered Species Act, but this is an emergency room measure with little to no preventative funding to recover species before they get to that point. Currently, only about $61 million annually is granted to states this purpose, whereas the Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies estimates that minimally $1.3 billion is needed to match the scale of recovery needs. For years, hunting and angling groups have called for other outdoor recreationists to foot a similar bill to the Pittman-Robertson excise taxes for non-game wildlife conservation – such as a backpack tax - as if we as hunters and anglers haven’t contributed just as much to the decline of non-game species through our daily actions as Americans resulting in habitat loss, wetland conversion, or the use of pesticides. Or that seeing nongame species like common loons or bald eagles isn’t just as valuable to our time outdoors as it is to someone not also trying to catch a fish or shoot a deer. The current wildlife crisis is a whole society crisis, not the sole responsibility of a subset of outdoor recreation users. As such, its solution must match the magnitude of the crisis, as National Wildlife Federation President and CEO Collin O’Mara says. And that’s what the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act does. The Recovering America’s Wildlife Act directs $1.3 billion to state wildlife agencies and $97.5 million to Tribal governments to fund wildlife restoration of species of greatest conservation need. Each state maintains a list of those species and needed recovery actions – often grouped by habitat type – in State Wildlife Action plans, updated every ten years. This act will actually provide the funding to implement those plans, for many states matching or even exceeding what they receive each year from Pittman-Robertson funding. For instance, Michigan would receive over $27 million annually under the Senate version of the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act; this year it received about $31 million from Pittman-Robertson funds. Passage of the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act would almost double Michigan’s federal funding for wildlife restoration. I could argue that the dedicated funding for mostly non-game species will also benefit game species sharing similar habitat – which it will – or that it will mean less has to be spent out of funds raised from hunting licenses or firearms excise taxes for wildlife restoration benefitting nongame species – which it will – but I’m not going to, because that would assume that as hunters and anglers, all we care about is what we can catch or shoot. And I don’t think that’s a very accurate description of our community, and it’s a rare hunter or angler who doesn’t also participate in another form of outdoor recreation. When I fly fish for northern pike up at my family’s Upper Peninsula cottage, seeing the bald eagles soar over the lake and hearing the loons call are as important to my outdoor experience as catching northern pike. When I surf at Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore, it wouldn’t be complete if I didn’t see a piping plover run along the beach or a monarch butterfly when I hike the dunes. And when I’m sitting against the base of a tree in the November deer woods in a northern Michigan state forest, a visit from a red-headed woodpecker breaks up the monotony of watching the trail below. Wildlife are the animating force of the woods and waters we haunt as outdoorsmen and outdoorswomen, and whether intended for our plate or creel or not, they give life to our experiences. With the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act, we are on the cusp of conservation history, finally dedicating the resources needed to recover America’s full diversity of wildlife, to have the impact on future generations that those legendary conservationists of past generations had on us, like National Wildlife Federation founder Ding Darling, who led the effort to pass Pittman-Robertson Act in 1937. It’s far from a sure thing, though. While it’s the most important wildlife conservation bill in generations, the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act still has to compete with every other issue Americans consider a priority for floor time in both chambers, despite its bipartisan support and the high number of congressional co-sponsors. Only time will tell whether our generation seizes this moment to conserve wildlife, or condemns us for letting the moment – and the wildlife - pass into history. I hope we choose the former. This article originally appeared in the May 2022 issue of Woods-N-Water News.

By Drew YoungeDyke The guide suggested a different fly and handed me one of his to use, as I didn’t have a close match in my fly box. I cast into the pool near the fallen log, stripped it back, felt the tug like I snagged a log with some bounce, and landed the biggest smallmouth bass I’ve ever caught. That’s exactly how we all envision fly fishing with guides, right? If that’s your expectation, though, then you’re setting yourself up for disappointment; not because it’s not a possibility, it’s just not how it always works. When you fish with guides, what you’re paying for more than anything is their knowledge of the specific water, the advice of their experience fishing it, and their skill in maneuvering the drift boat to put you in likely places and good position to catch fish; however, the actual catching of fish is up to you, and neither one of you control the fish. In March, I had the opportunity to fly fish for smallmouth bass on a west Michigan river with two skillful Michigan fishing guides – Ted Kushion and Tom Werkman - as they scouted some water together. A trip like this accomplishes several things to help guides better serve their future clients. Aside from knowing where fish in that stretch of water like to hang out in certain conditions and at certain times of the year, fishing with other guides allows them to share tactics, strategies, knowledge, and experience with each other. And by having a full boat, we always had two lines in the water testing different flies, depths, and retrievals until we found what the fish liked. The forecast called for rain throughout the day with temperatures in the 40s, so we didn’t really know what to expect as far as actually catching fish. After a slow and fishless morning, our spirits were buoyed when Tom caught an accidental northern pike. They were out of season so he quickly released it, but at least fish were starting to eat! Soon after, Ted caught and released two nice smallmouth on black leech patterns with dumbbell eyes, using a faster retrieve than Tom or I had been. The bite was on! I was trying out some recent ties – a weighted white and brown Game Changer called the Sleeper Sculpin and a big olive Bucktail Game Changer that swam and kicked just right – but I hadn’t landed a fish. I narrowly missed a subsurface take on the Bucktail Game Changer as I saw a dark green head emerge right behind it, but in my excitement stripped the fly right out of its mouth instead of letting it pause for the take. However, I was pretty sure it was a northern pike instead of a smallmouth, so that was okay. While northern pike are my favorite species and I get excited about any northern pike fly fishing encounter, the season on them had closed for spawning so I only wanted to catch smallmouth that day. My Sleeper Sculpin was probably the wrong color, and the buoyant Bucktail Game Changer wasn’t getting down as far as Ted’s leech patterns, even with my sink tip-line. He handed me one of his flies – a black rabbit strip leech pattern with weighted dumbbell eyes and red rubber legs. I tied it on, asked the ancient Finnish water god Ahti for some luck, and soon hooked up with a fat, approximately 17-inch smallmouth! We didn’t measure it, but it was easily my biggest smallmouth to date. Ted rowed us to another spot on the river and Tom tied on a Low Water Cray pattern that caught five smallies in a row, including a beautiful golden-bronze tank with distinct dark stripes. I felt a tug on my line and stripped it toward the boat as a juvenile pike shook, rattled, and rolled. Ted netted it and I quickly released it. I cast again and again. A smallmouth followed but turned away from my fly. I cast again and felt that heavy tug, as a fat smallmouth fought its way into Ted’s net, about the same size as my first smallie. This one we measured precisely at 17 inches before releasing it. The bite window seemed to close as a storm rolled in. I tried rowing the drift boat and found increased admiration for the ability of Ted and Tom to maneuver with the skill they did. I typically fish solo out of a 15-foot canoe, or row and old 14-foot aluminum boat up at our Upper Peninsula cottage, but I’d never rowed a drift boat. None of it felt intuitive, and while I’m pretty adept at, for instance, mending my canoe float with a paddle in one hand and a fly rod in the other, I was pretty slow at rowing the drift boat, as the wind pushed me all over. It takes practice, coordination, experience, skill, strength, and endurance to row it for a full day float, and to maneuver and keep it in position for anglers to cast where fish might be. After a lightning strike, Ted wisely took over and rowed us to our takeout location. It was a great day of fishing – especially for March – as collectively we landed nine smallmouth bass and two accidental northern pike, and personally I caught my two largest smallmouth bass and a northern pike. It’s what you envision when fly fishing with guides, but it’s not always what happens and shouldn’t be expected. If we had only fished a half day, or kept trying the same flies, retrieves, and depths, we would have been skunked. We tried different patterns, different depths, and different retrieves until we found what worked – and the bite window turned on. Ted and Tom took water temperature readings throughout the day so they could better understand how that might have factored into the bite window. They noted that where we caught fish wasn’t necessarily in the exact places where they anticipated that we would catch fish. And they added all of that to their store of knowledge and experience as guides that they can draw upon to have better odds of putting paying clients on fish. Then they booked a trip the next week with James Hughes, head guide at Schultz Outfitters in Ypsilanti, to learn even more from him. When you fish with guides, there are some things that you should expect. You should expect that they have a logistical plan for the day, a safety plan, are proficient with their craft, and are knowledgeable about the water you’re on and the fish you’re pursuing. You should expect that whatever additional elements they advertised or you agreed to are met – like lunch or beverages. You should expect that they’ll do their best to put you in likely spots where fish might be and to share their knowledge with you to help you have the best chance to catch fish that day. However, they can’t control where the fish will be and they can’t catch the fish for you. Your ability to cast, to set the hook, to control the fish, and especially to listen to your guide are up to you. And don’t ask them to take you to their secret spot they don’t show to other clients; it doesn’t exist. They make their living by helping you have the best odds of catching fish that day, and if they know where fish are likely to be, that’s where they’re taking you, anyway. Finally, whether you get skunked or catch the best fish of your life, tip your guides based on the service they provided, not on the fish you did or didn’t catch. Fishing with guides is a great way to learn more about the water, the fish, the conditions, and improving your angling craft. They don’t have to be casting coaches, but just watching what they do and listening to their observations and advice improves your store of fly fishing knowledge. If you get the opportunity to fish with guides, entering the day with the proper expectations and mindset will yield a fishing experience that makes you a better angler, regardless of what you catch that day. And who knows? You might just catch the biggest smallmouth of your life, anyway. Contact Tom Werkman at WerkmanOutfitters.com and Ted Kushion at FlatRiverOutfitters.com. Originally published in the April 2022 issue of Woods-N-Water News

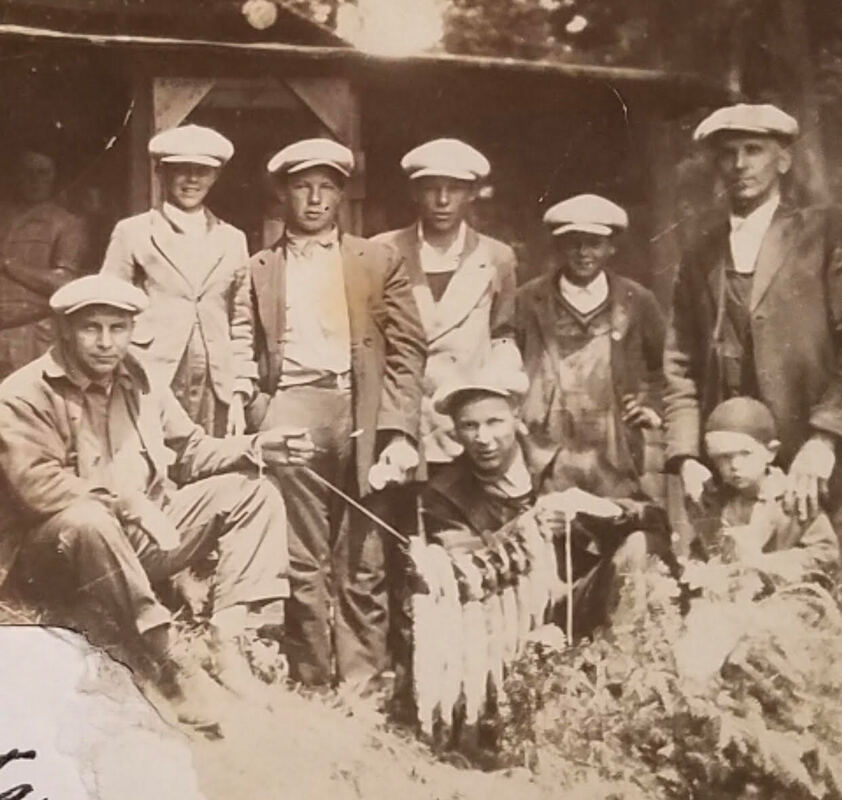

Drew YoungeDyke Spring blooms hope in the heart of every angler; no matter the past season’s frustrations, a new season of fishing arrives with warmer weather, ice out, post spawn and spawning fish, and optimism envisioned in every cast. Year round catch-and-release for many species has scarcely dimmed the traditions around the first day for keeper season for many species, even if we mostly catch-and-release, anyway. Michigan’s traditional trout opener on the last Saturday in April holds a rich history. Robert Traver (pen name of former Michigan Supreme Court Justice John D. Voelker and author of Anatomy of a Murder) wrote “Trout Madness,” a bible for any Michigan fly angler, which begins with the essay “First Day” recounting Traver’s opening day exploits chasing trout in the Upper Peninsula. “The day is invested with its own special magic, a magic that nothing can dispel,” Traver wrote. “It is the signal for the end of the long winter hibernation, the widening of prison doors, the symbol of one of nature’s greatest miracles, the annual unlocking of spring.” Traver’s trout opener journal entries from 1936 to 1952 are as memorable for stuck fish cars and frozen ponds as for trout, but much like the opening day of deer season, the traditions of deer camp often are more memorable than the empty buck poles. Jim Harrison - the late author, poet, and angler - grew up and lived in Michigan most of his life. In a 1971 article, “A Plaster Trout in Worm Heaven” – contained in his “Just Before Dark” collection of nonfiction - he describes why the trout opener doesn’t always produce the best trout fishing. “The first day always seems to involve resolute masochism; if it isn’t unbearably cold, then the combination of rain and warmth manages to provide maximal breeding conditions for mosquitoes, and they cloud and swarm around your head, crawl up your sleeves and down your neck, despite the most potent and modern chemicals.” A couple years ago I joined some friends for a Trout Camp up in the Pigeon River Country for opening day. We camped out the night before with snow falling and frigid temperatures, warmed up by beaver stew and moonshine. The next morning, I realized I’d left my reel at home in Ann Arbor – four hours away – so I joined the Headwaters Chapter of Trout Unlimited’ s annual Pancake Breakfast at the forest headquarters without so much as wetting a line. The Pigeon River Country Discovery Center at the headquarters contains an exhibit about Ernest Hemingway, who spent his summers in northern Michigan as a youth and often fly fished in the Pigeon River Country and the Upper Peninsula. The exhibit contained an excerpt from a letter he’d written inviting friends to a similar fish camp in the Pigeon River Country a hundred years earlier, which he referred to as the Pine Barrens. “Picture us on the Barrens, beside the river with a camp fire and the tent and a good meal in our bellies smoking a pill with a good bottle of grog.” That’s the spirit of the trout opener whether any fish are caught or not. Spring fishing openers are about the optimism of looking forward to warmer summer days on the water. Tom McGuane – perhaps the finest fishing writer ever – also grew up in Michigan and used to fish in the Pigeon River Country, too. In “Small Streams in Michigan” - contained in his collection of nonfiction fishing writing, “The Longest Silence” - he describes fishing the Pigeon, Black, and Sturgeon Rivers: “I’d pick a stretch of the Pigeon or the Black for early fishing, wade the oxbow between the railroad bridges on the Sturgeon in the afternoon. Then, in the evening, I’d head for a wooden bridge over the Sturgeon near Wolverine.” I’m mostly a failed trout angler. After fifteen years of catching more tree branches than trout on a fly, I was almost ready to give up on serious fly fishing until John Cleveland told me about fly fishing for northern pike during a Michigan Outdoor Writers Association conference in 2018. That lit something in me, and since then I’ve been obsessed with it, gearing up with heavy weight fly rods and lines to cast giant bucktail streamers. It led me into fly tying, then into more purposeful and successful fly fishing for the other species that inhabit pike waters like bluegill, crappie, perch, and bass. The obsession has become so complete that I don’t even bow hunt anymore because it cuts into my fall pike fishing time. The Lower Peninsula pike opener is also the last Saturday in April, like the trout opener, but I have the Upper Peninsula pike opener of May 15 circled on my calendar. My family has a cottage in Gogebic County on a lake dominated by northern pike, where I caught my first two pike on the fly in 2019. My great grandpa, who bought the old logging camp bunkhouse and deer camp shack to convert into a family cottage in the 1950s, used to host his family fish camp there and before that on a little lake across the border in Wisconsin containing musky and northern pike. A fish camp on May 15 would provide perfect symmetry to the annual deer camp firearm opener on November 15, being perfectly six months apart, dividing the year in two. I hosted some friends for pike camp at the cottage in the September before the pandemic struck and it felt like I was on to something. Reviving that fish camp tradition – more than a century after he started it – would be like coming out of that long winter hibernation that Traver wrote about. Maybe I’m just looking for that magic that nothing can dispel. A magic that would allow me to fish with my ancestors, in whatever weather comes, and maybe share a bottle of grog like Hemingway, even if I’m the only one on the lake. Originally published in the March 2022 issue of Woods-N-Water News

By Drew YoungeDyke Throughout the winter, I have dutifully tied flies to refill boxes for the species I expect to fish for most in the coming year, like bluegill and bass, but there is only one fish that I obsess over all year, only one fish that I tie more flies for than I could ever hope to use in the coming year, one fish for which I seek out countless YouTube videos and re-read the same articles about online and in past issues of outdoor magazines: northern pike. Northern pike are a coolwater species that haunt the edges of weed beds and structure to ambush prey that swims by looking like an easy meal – and everything looks like an easy meal to northern pike. Durable flies made of just one or two materials can be effective for catching northern pike, provided that they present the profile of something pike eat and have a head that pushes water to make the tail wiggle. My two favorite flies to tie for pike follow this simple theory and use just one or two materials, in addition to the hook and thread: Bucktail Deceivers and Pike Bunnies. The bucktail deceiver is an all-bucktail variation by Bob Popovics of Lefty Kreh’s Deceiver, originally a saltwater fly intended to resemble baitfish. Pike Bunnies are simple but effective streamers consisting of a rabbit zonker strip tail and a palmered zonker strip head. A couple strips of flash or glue-on eyes can be added to either. Sometimes I’ll mix them up, too, with a rabbit strip tail and a bucktail head, or add a tungsten conehead to either. I fish both of these flies with a 9-wt Orvis Clearwater rod and Scientific Anglers floating , sink-tip, or full sinking line, depending on conditions and how deep I want to fish them, connected with a Scientific Anglers Stealth Predator leader, cast over and next to weeds beds and structure, depending on depth, and stripped back at varying speeds, pausing every few strips to let the fly turn like a wounded fish. It’s important to use a strip set with northern pike, rather than raising your rod tip like in trout fishing, and never lip-grip a northern pike like a bluegill or bass if you value your fingers! Bucktail Deceiver This past fall, I fished the Huron River on a cold and wet October day. I paddled my canoe up the river and floated back down, casting a 2/0 bucktail deceiver near shoreline cover and stripping it back. As I floated along, one spot just looked…right. I landed the fly right where I wanted, stripped it back, and whomp! The underwater strike was the unmistakable attack of a northern pike. I strip set the hook and worked the northern back to my canoe, the adrenaline still pulsing through me as I took a couple photos of the 30-incher with my iPhone and reached down to release it boatside, having forgot my net. I had tied the 6-inch, 2/0 white and natural bucktail deceiver last spring with just such a scenario in mind. A couple weeks later, I got a chance to fish again and connected on a 24-inch northern on the same stretch of river with an identical fly. This is the streamer I’m focused on tying most this winter in a variety of pikey colors. My pike fly box is well stocked with all-black, black/orange, all-white, and white/natural flies, so I’m tying red/white, chartreuse/white, orange/white, and blue/white variations this winter. To tie a bucktail streamer for northern pike, use a streamer hook from sizes 2/0 to 6/0. I use thick 210 thread and the Loon hair scissors for more precise cuts on the bucktail, and either superglue, Loon UV resin, or Wapsi Fly-Tyers Zment on each tie of bucktail for added durability. Working from the tail to the head, use hair from the tip of the tail, working toward the front; hairs to the front are more hollow, and will flair more when tightened. Gradually tie in thicker clumps of hair as you get to the head, too, allowing enough room to tie it all down before the eye. After starting your thread, cut a long, thin clump of hair from the end of the tail. Grasp it tightly in the middle and pull out the short hairs. Tie it in just before the bend of the hook. Snip the excess hair in front of the tie and add a drop of superglue or UV resin. Snip a slightly thicker clump of hair from just a little further down the tail, tie in, snip, add glue, and repeat. You can add a couple strips of flash to any of the ties. This is all you do to tie this fly, gradually increasing the thickness of the ties as you move to the front and using hair from progressively closer to the front of the bucktail. The thicker head will push water to move the thinner tail. Most of my deceivers end up in the 5 to 8-inch range, depending on the length of bucktail and size of the hook. Sometimes I’ll finish the fly with a hollow tie, but mostly this winter I’m working on improving my proportions and the overall silhouette of these simple but effective flies. Glue-on eyes can also be added, buy mine rarely last more than one strike so I don’t often add them anymore to pike flies. Bucktail deceivers resemble baitfish in the water, and the bucktail undulations move and flow with an enticing reality. Strip them at varying speeds, stopping every few strips to let the fly fall, flow, turn sideways and jackknife; this is often when pike will strike. However, be ready for a strike as soon as they land. As you progress in your fly-tying, you can apply the same concept of taper to tie a bucktail version of Blane Chocklett’s revolutionary Game Changer fly. Pike Bunnies One of the people I reached out to when I first started fly-fishing for northern pike out was fellow outdoor writer Tim Mead. Tim has fly-fished for northern pike out of a float tube on lakes throughout the Upper Peninsula and relies on simple, durable streamers. “For pike, I've given up on feathers,” Tim recommends. “They don't last more than a couple of fish. For me: zonker strips. They last lots longer. The two 50-plus-inch pike I’ve caught were both on zonker strip streamers.” Pike bunnies – also called pike snakes – are perhaps the simplest pike fly to tie. I have several in olive, and this winter I’m tying in the classic pike colors of red/white, purple/black, and red/black, and all-black. Like the bucktail streamer, the idea is to use a bulkier head to push water that makes the skinnier tail wiggle and move. After starting the thread, tie in a strip of bucktail, ensuring the hair flows toward the back. I taper the strip at the tie-in point, as well, and glue down the tie or add UV resin. A couple lengths of flash could be tied in here, as well, the length of the tail. The length of the tail is up to you and determines the length of your fly; I usually cut mine at 4 or 5 inches. Much longer, the tail tends to foul the hook for me. Next, tie in the end of another zonker strip; if you’re making it two-tone, this is where you switch colors. Move the thread up to the head of the fly, allowing room to tie in before the hook eye. Add a drop of superglue, UV resin, or head cement to the back tie-in. Palmer wrap the zonker strip forward, taking time to keep the strip tight to the hook and brushing back the hair so it doesn’t get caught under the strip. Tie it off at the front of the hook, whip finish, and add UV resin or head cement to the head tie-in. Some add glue-on eyes to the head tie-in, as well, though I don’t. And that’s it! An articulated variation of the pike bunny is John Cleveland’s “Bunny Buster” fly, which also uses a flashy bead head. I’ve tied some flies this winter that are a combination of the two above, with a zonker strip tail and a bucktail head. As in the bucktail deceiver, I’m mindful of the taper and use the hollow hair from the front of the bucktail to flair the head and push more water to make the tail move. Inspired by Upper Hand Brewery’s Sisu Stout seasonal craft beer, I tied one on a 2/0 streamer hook with a white zonker strip tail, some white/pearl polar flash, and a reverse-tied blue bucktail head (the colors of Finland’s flag) that I call the Sisu Streamer, superglued at every tie to withstand multiple pike strikes. Sisu is a good concept to keep in mind in tying and fishing flies for northern pike. Sisu is the Finnish concept of enduring tough conditions with grit and simple determination over the long haul. Simple, durable flies will endure the tough conditions of multiple vicious northern pike strikes, and you’ll need lots of sisu to double haul cast after cast of heavy bucktail and zonker strip streamers in sometimes tough conditions to catch them. Fly tying doesn’t have to be complicated or intimidating; by starting with simple but effective flies for warm and coolwater fish like panfish, bass, and northern pike, you can tie flies that catch fish with confidence while you develop your fly-tying skillset. As you advance in fly-tying, you can use the skills you develop with these simple flies to tie more complex patterns, but you’ll always keep these staples in your fly box because they catch fish. There is nothing more satisfying in fishing, in my opinion, than catching a fish on a fly that you tied yourself. Tight wraps and tight lines. Originally published in the February 2022 issue of Woods-n-Water News

By Drew YoungeDyke With a snowstorm in the forecast on a cold winter day, it’s natural to think about the opposite: a bright sunny day in June, green leaves reflected on the water, and stripping a popper next to a submerged log. Pop, pop, whoosh! A largemouth smashes the surface and tugs the fly deep into the cabbage, each twist sending vibrations down the tight 8-wt line as it tries to shake it off. The fight makes you think it’s a fish worthy of sparkle-boat plastered with sponsor logos as you kick or paddle your float tube, canoe or kayak over to it and net the bass, cabbage and all. Even a small bass leaves you smiling as you take a quick picture and release it. This scene is what bass fishing is to me, and it’s the experience that I’m tying flies for this winter while restocking my bass box. As voracious eaters, there are numerous effective patterns for largemouth and smallmouth bass, but this winter I’m focusing on the simplest patterns using the least materials, especially a variety of poppers and Clouser minnows, which are simple to tie and that I’ve had the most success with on bass. Before I started tying my own flies, I had the most success with the appropriately-named Orvis Bass Popper. Years before I started tying, I had bought a package of Zudbubbler popper bodies with the intention of learning to tie that I found in my old tackle bag, so I started tying poppers with those. While my skills were still developing, the flies floated well and popped hard and despite the sloppiness of my early ties, actually caught a few fish! One tied with yellow/black grizzly hackles I dubbed the “Killa Bee” in honor of the Wu-Tang Clan, and it even caught a few before I lost it. This winter I may buy some additional foam popper bodies but, to start, I’m going old-school by using actual wine bottle corks to make my poppers. The recipe is simple. Use a medium size streamer hooks up to size 1/0 – or even worm hooks with the barb pinched down. I wrap thread along the shank of the hook to provide a base to glue to for the cork body, which I cut into shapes with an open face, sloping back, and a range of widths with a flat bottom. I tie on a tail of either marabou, bucktail, or zonker strip at the beginning of the bend of the hook, followed by a collar of bucktail or hackle. I take one length of round rubber or sili-leg material, fold itin half, and tie it around the shank at its midpoint, leaving enough room in front of it for the popper body. Snip the resulting loop in the rubber legs to leave two legs extending down from each side. Next, cut a slit on the bottom of the cork body for the hook to slide into, extending about a third into the body. Next, apply superglue to the slot and fit it over the hook – ensuring the eye isn’t covered – and let it dry. The popper body can be left alone or finished with more detail by using a sharpie to draw eyes, spots and/or stripes, or by gluing on stick-on eyes. I’ve finished a few using Loon UV Hard finish in both clear and black, brushing a coating over the cork popper. Experiment with different colors; I’m focusing on olive, chartreuse, yellow, natural, white, and black this winter. The point of the popper is to provide a lot of topwater action, angering the bass into striking from its cover, with explosive topwater takes. It’s as fun as fly-fishing gets, in my opinion. If it floats, pops with each little strip, and you’re stripping it over cover in almost any small inland warmwater lake in Michigan, then each pop holds the anticipation of a strike. I usually fish these on an 8-wt floating line, or even my 9-wt floating line for bigger poppers to ensure a smooth turnover. While it’s not a stealth game with poppers, I still want to deliver the fly accurately to the spot I want without spooking the bass that may be in cover underneath. I want it take on the strip-pop, but be ready for a strike as soon as it lands on the water- I’ve had plenty of those, too. As the summer gets warmer and bass move to deeper cover, I switch to Clouser Minnows. This wispy little bucktail fly was developed for saltwater by the legendary Bob Clouser but has proven effective for multiple freshwater species including bass and northern pike. I’ve caught some nice crappies with Clouser minnows, too. And like all the flies I’m tying this winter, it is simple to tie and made with relatively few materials: a hook, thread, bucktail, nontoxic dumbbell eyes, and flash. These are usually tied two-tone with the darker color on top; chartreuse/white, olive/white, and red/white for pike are usually what I tie. I fish these with a floating 8-wt, a sink-tip, or a full sinking line depending on how deep I want to get. Again, use medium size streamer hooks up to size 1/0 or 2/0. It’s important to remember that the Clouser will ride hook-up, so if you do not have a rotating vice, you’ll be tying it upside down, so to speak. Wrap the thread from the hook eye to about halfway between the hook eye and the point of the hook. This is where the dumbbell eyes will be tied in. For tying in dumbbell eyes, I recommend watching a few YouTube tutorials to see some different options for holding them secure. With the hook down, tie in the dumbbell eyes on top of the hook shank. I always use nontoxic, nonlead dumbbell eyes because should you lose the fly or a fish breaks it off, nontoxic eyes will not poison eagles or loons as lead will. I use a combination of diagonal cross wraps, wraps in front of and behind the eyes, and wraps under the eyes, above the hook shank, to tighten them. End the wrap in front of the hook eye and make sure they’re level. At this point I add a drop of UV clear, head cement, superglue under the hook shank for extra security. Select a pencil-width of bucktail from the middle of the bucktail, Remove the short hairs and tie it in at a 45-degree angle in front of the dumbbell eyes, tying down with wraps up to the hook eye and back. Loop the thread under the dumbbell eyes and tie the bucktail down behind the eyes with a couple tight wraps, then a few open spiral wraps down the hook shank and back up to the eye of the hook. Next, tie in a couple strands of flash, folded in half around the tying thread, the length of the bucktail, along the belly of the fly. Finally, add a similar or slightly larger clump of the darker bucktail and tie it in under the fly in front of the dumbbell eyes, and whip finish. I’ll add UV clear fly finish or head cement to the head of the fly, as well. When riding hook up, the darker color should be on top, imitating a minnow. Cork bass poppers and Clouser minnows are two of the simplest patterns to tie to catch bass on the fly. If you’re a beginner fly-tyer, these are great ones to learn on to develop confidence and catch fish. Woolly buggers can also be effective. Watch YouTube videos to see how the flies are tied, as well as books like The Orvis Fly-Tying Guide by Tom Rosenbauer. Alvin DeDeaux also has a great YouTube series on “guide flies” that he ties for Guadalupe Bass in Texas using very simple materials. If you’re a more advanced fly tyer, I’d recommend checking out the Schultz Outfitters YouTube page for tying some of their patterns, Mad River Outfitters out of Ohio, or Blane Chocklett’s Game Changer. Next month, I’ll describe some simple northern pike flies to tie for voracious warmwater action. |

AUTHOR

Drew YoungeDyke is an award-winning freelance outdoor writer and a Director of Conservation Partnerships for the National Wildlife Federation, a board member of the Outdoor Writers Association of America, and a member of the Association of Great Lakes Outdoor Writers and the Michigan Outdoor Writers Association.

All posts at Michigan Outside are independent and do not necessarily reflect the views of NWF, Surfrider, OWAA, AGLOW, MOWA, the or any other entity. ARCHIVES

June 2022

SUBJECTS

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed