|

Originally published in the April 2022 issue of Woods-N-Water News

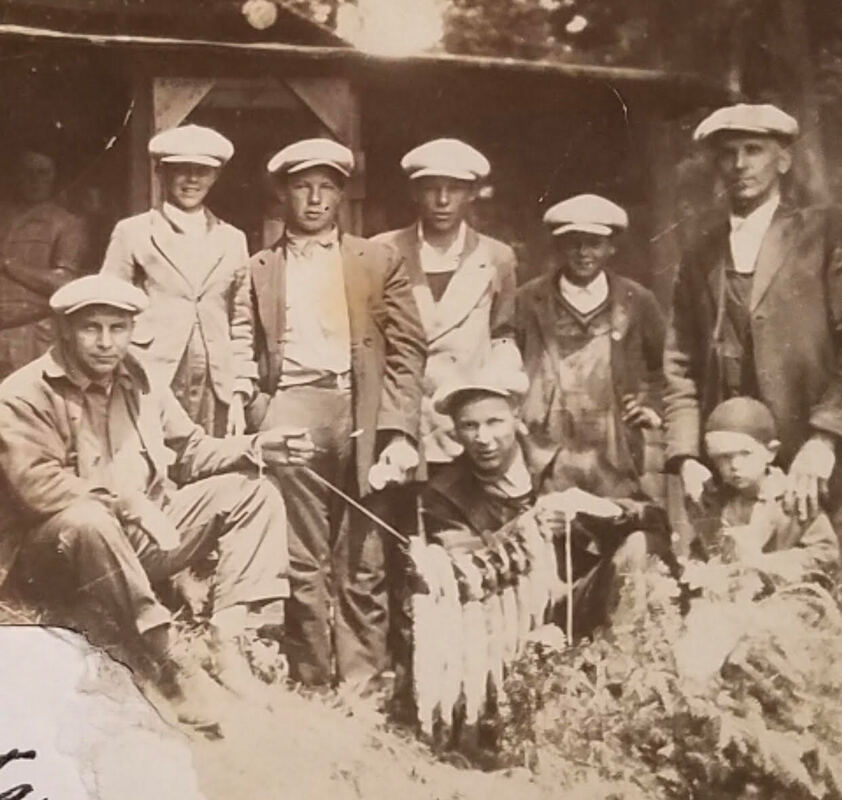

Drew YoungeDyke Spring blooms hope in the heart of every angler; no matter the past season’s frustrations, a new season of fishing arrives with warmer weather, ice out, post spawn and spawning fish, and optimism envisioned in every cast. Year round catch-and-release for many species has scarcely dimmed the traditions around the first day for keeper season for many species, even if we mostly catch-and-release, anyway. Michigan’s traditional trout opener on the last Saturday in April holds a rich history. Robert Traver (pen name of former Michigan Supreme Court Justice John D. Voelker and author of Anatomy of a Murder) wrote “Trout Madness,” a bible for any Michigan fly angler, which begins with the essay “First Day” recounting Traver’s opening day exploits chasing trout in the Upper Peninsula. “The day is invested with its own special magic, a magic that nothing can dispel,” Traver wrote. “It is the signal for the end of the long winter hibernation, the widening of prison doors, the symbol of one of nature’s greatest miracles, the annual unlocking of spring.” Traver’s trout opener journal entries from 1936 to 1952 are as memorable for stuck fish cars and frozen ponds as for trout, but much like the opening day of deer season, the traditions of deer camp often are more memorable than the empty buck poles. Jim Harrison - the late author, poet, and angler - grew up and lived in Michigan most of his life. In a 1971 article, “A Plaster Trout in Worm Heaven” – contained in his “Just Before Dark” collection of nonfiction - he describes why the trout opener doesn’t always produce the best trout fishing. “The first day always seems to involve resolute masochism; if it isn’t unbearably cold, then the combination of rain and warmth manages to provide maximal breeding conditions for mosquitoes, and they cloud and swarm around your head, crawl up your sleeves and down your neck, despite the most potent and modern chemicals.” A couple years ago I joined some friends for a Trout Camp up in the Pigeon River Country for opening day. We camped out the night before with snow falling and frigid temperatures, warmed up by beaver stew and moonshine. The next morning, I realized I’d left my reel at home in Ann Arbor – four hours away – so I joined the Headwaters Chapter of Trout Unlimited’ s annual Pancake Breakfast at the forest headquarters without so much as wetting a line. The Pigeon River Country Discovery Center at the headquarters contains an exhibit about Ernest Hemingway, who spent his summers in northern Michigan as a youth and often fly fished in the Pigeon River Country and the Upper Peninsula. The exhibit contained an excerpt from a letter he’d written inviting friends to a similar fish camp in the Pigeon River Country a hundred years earlier, which he referred to as the Pine Barrens. “Picture us on the Barrens, beside the river with a camp fire and the tent and a good meal in our bellies smoking a pill with a good bottle of grog.” That’s the spirit of the trout opener whether any fish are caught or not. Spring fishing openers are about the optimism of looking forward to warmer summer days on the water. Tom McGuane – perhaps the finest fishing writer ever – also grew up in Michigan and used to fish in the Pigeon River Country, too. In “Small Streams in Michigan” - contained in his collection of nonfiction fishing writing, “The Longest Silence” - he describes fishing the Pigeon, Black, and Sturgeon Rivers: “I’d pick a stretch of the Pigeon or the Black for early fishing, wade the oxbow between the railroad bridges on the Sturgeon in the afternoon. Then, in the evening, I’d head for a wooden bridge over the Sturgeon near Wolverine.” I’m mostly a failed trout angler. After fifteen years of catching more tree branches than trout on a fly, I was almost ready to give up on serious fly fishing until John Cleveland told me about fly fishing for northern pike during a Michigan Outdoor Writers Association conference in 2018. That lit something in me, and since then I’ve been obsessed with it, gearing up with heavy weight fly rods and lines to cast giant bucktail streamers. It led me into fly tying, then into more purposeful and successful fly fishing for the other species that inhabit pike waters like bluegill, crappie, perch, and bass. The obsession has become so complete that I don’t even bow hunt anymore because it cuts into my fall pike fishing time. The Lower Peninsula pike opener is also the last Saturday in April, like the trout opener, but I have the Upper Peninsula pike opener of May 15 circled on my calendar. My family has a cottage in Gogebic County on a lake dominated by northern pike, where I caught my first two pike on the fly in 2019. My great grandpa, who bought the old logging camp bunkhouse and deer camp shack to convert into a family cottage in the 1950s, used to host his family fish camp there and before that on a little lake across the border in Wisconsin containing musky and northern pike. A fish camp on May 15 would provide perfect symmetry to the annual deer camp firearm opener on November 15, being perfectly six months apart, dividing the year in two. I hosted some friends for pike camp at the cottage in the September before the pandemic struck and it felt like I was on to something. Reviving that fish camp tradition – more than a century after he started it – would be like coming out of that long winter hibernation that Traver wrote about. Maybe I’m just looking for that magic that nothing can dispel. A magic that would allow me to fish with my ancestors, in whatever weather comes, and maybe share a bottle of grog like Hemingway, even if I’m the only one on the lake. Originally published in the March 2022 issue of Woods-N-Water News

By Drew YoungeDyke Throughout the winter, I have dutifully tied flies to refill boxes for the species I expect to fish for most in the coming year, like bluegill and bass, but there is only one fish that I obsess over all year, only one fish that I tie more flies for than I could ever hope to use in the coming year, one fish for which I seek out countless YouTube videos and re-read the same articles about online and in past issues of outdoor magazines: northern pike. Northern pike are a coolwater species that haunt the edges of weed beds and structure to ambush prey that swims by looking like an easy meal – and everything looks like an easy meal to northern pike. Durable flies made of just one or two materials can be effective for catching northern pike, provided that they present the profile of something pike eat and have a head that pushes water to make the tail wiggle. My two favorite flies to tie for pike follow this simple theory and use just one or two materials, in addition to the hook and thread: Bucktail Deceivers and Pike Bunnies. The bucktail deceiver is an all-bucktail variation by Bob Popovics of Lefty Kreh’s Deceiver, originally a saltwater fly intended to resemble baitfish. Pike Bunnies are simple but effective streamers consisting of a rabbit zonker strip tail and a palmered zonker strip head. A couple strips of flash or glue-on eyes can be added to either. Sometimes I’ll mix them up, too, with a rabbit strip tail and a bucktail head, or add a tungsten conehead to either. I fish both of these flies with a 9-wt Orvis Clearwater rod and Scientific Anglers floating , sink-tip, or full sinking line, depending on conditions and how deep I want to fish them, connected with a Scientific Anglers Stealth Predator leader, cast over and next to weeds beds and structure, depending on depth, and stripped back at varying speeds, pausing every few strips to let the fly turn like a wounded fish. It’s important to use a strip set with northern pike, rather than raising your rod tip like in trout fishing, and never lip-grip a northern pike like a bluegill or bass if you value your fingers! Bucktail Deceiver This past fall, I fished the Huron River on a cold and wet October day. I paddled my canoe up the river and floated back down, casting a 2/0 bucktail deceiver near shoreline cover and stripping it back. As I floated along, one spot just looked…right. I landed the fly right where I wanted, stripped it back, and whomp! The underwater strike was the unmistakable attack of a northern pike. I strip set the hook and worked the northern back to my canoe, the adrenaline still pulsing through me as I took a couple photos of the 30-incher with my iPhone and reached down to release it boatside, having forgot my net. I had tied the 6-inch, 2/0 white and natural bucktail deceiver last spring with just such a scenario in mind. A couple weeks later, I got a chance to fish again and connected on a 24-inch northern on the same stretch of river with an identical fly. This is the streamer I’m focused on tying most this winter in a variety of pikey colors. My pike fly box is well stocked with all-black, black/orange, all-white, and white/natural flies, so I’m tying red/white, chartreuse/white, orange/white, and blue/white variations this winter. To tie a bucktail streamer for northern pike, use a streamer hook from sizes 2/0 to 6/0. I use thick 210 thread and the Loon hair scissors for more precise cuts on the bucktail, and either superglue, Loon UV resin, or Wapsi Fly-Tyers Zment on each tie of bucktail for added durability. Working from the tail to the head, use hair from the tip of the tail, working toward the front; hairs to the front are more hollow, and will flair more when tightened. Gradually tie in thicker clumps of hair as you get to the head, too, allowing enough room to tie it all down before the eye. After starting your thread, cut a long, thin clump of hair from the end of the tail. Grasp it tightly in the middle and pull out the short hairs. Tie it in just before the bend of the hook. Snip the excess hair in front of the tie and add a drop of superglue or UV resin. Snip a slightly thicker clump of hair from just a little further down the tail, tie in, snip, add glue, and repeat. You can add a couple strips of flash to any of the ties. This is all you do to tie this fly, gradually increasing the thickness of the ties as you move to the front and using hair from progressively closer to the front of the bucktail. The thicker head will push water to move the thinner tail. Most of my deceivers end up in the 5 to 8-inch range, depending on the length of bucktail and size of the hook. Sometimes I’ll finish the fly with a hollow tie, but mostly this winter I’m working on improving my proportions and the overall silhouette of these simple but effective flies. Glue-on eyes can also be added, buy mine rarely last more than one strike so I don’t often add them anymore to pike flies. Bucktail deceivers resemble baitfish in the water, and the bucktail undulations move and flow with an enticing reality. Strip them at varying speeds, stopping every few strips to let the fly fall, flow, turn sideways and jackknife; this is often when pike will strike. However, be ready for a strike as soon as they land. As you progress in your fly-tying, you can apply the same concept of taper to tie a bucktail version of Blane Chocklett’s revolutionary Game Changer fly. Pike Bunnies One of the people I reached out to when I first started fly-fishing for northern pike out was fellow outdoor writer Tim Mead. Tim has fly-fished for northern pike out of a float tube on lakes throughout the Upper Peninsula and relies on simple, durable streamers. “For pike, I've given up on feathers,” Tim recommends. “They don't last more than a couple of fish. For me: zonker strips. They last lots longer. The two 50-plus-inch pike I’ve caught were both on zonker strip streamers.” Pike bunnies – also called pike snakes – are perhaps the simplest pike fly to tie. I have several in olive, and this winter I’m tying in the classic pike colors of red/white, purple/black, and red/black, and all-black. Like the bucktail streamer, the idea is to use a bulkier head to push water that makes the skinnier tail wiggle and move. After starting the thread, tie in a strip of bucktail, ensuring the hair flows toward the back. I taper the strip at the tie-in point, as well, and glue down the tie or add UV resin. A couple lengths of flash could be tied in here, as well, the length of the tail. The length of the tail is up to you and determines the length of your fly; I usually cut mine at 4 or 5 inches. Much longer, the tail tends to foul the hook for me. Next, tie in the end of another zonker strip; if you’re making it two-tone, this is where you switch colors. Move the thread up to the head of the fly, allowing room to tie in before the hook eye. Add a drop of superglue, UV resin, or head cement to the back tie-in. Palmer wrap the zonker strip forward, taking time to keep the strip tight to the hook and brushing back the hair so it doesn’t get caught under the strip. Tie it off at the front of the hook, whip finish, and add UV resin or head cement to the head tie-in. Some add glue-on eyes to the head tie-in, as well, though I don’t. And that’s it! An articulated variation of the pike bunny is John Cleveland’s “Bunny Buster” fly, which also uses a flashy bead head. I’ve tied some flies this winter that are a combination of the two above, with a zonker strip tail and a bucktail head. As in the bucktail deceiver, I’m mindful of the taper and use the hollow hair from the front of the bucktail to flair the head and push more water to make the tail move. Inspired by Upper Hand Brewery’s Sisu Stout seasonal craft beer, I tied one on a 2/0 streamer hook with a white zonker strip tail, some white/pearl polar flash, and a reverse-tied blue bucktail head (the colors of Finland’s flag) that I call the Sisu Streamer, superglued at every tie to withstand multiple pike strikes. Sisu is a good concept to keep in mind in tying and fishing flies for northern pike. Sisu is the Finnish concept of enduring tough conditions with grit and simple determination over the long haul. Simple, durable flies will endure the tough conditions of multiple vicious northern pike strikes, and you’ll need lots of sisu to double haul cast after cast of heavy bucktail and zonker strip streamers in sometimes tough conditions to catch them. Fly tying doesn’t have to be complicated or intimidating; by starting with simple but effective flies for warm and coolwater fish like panfish, bass, and northern pike, you can tie flies that catch fish with confidence while you develop your fly-tying skillset. As you advance in fly-tying, you can use the skills you develop with these simple flies to tie more complex patterns, but you’ll always keep these staples in your fly box because they catch fish. There is nothing more satisfying in fishing, in my opinion, than catching a fish on a fly that you tied yourself. Tight wraps and tight lines. By Drew YoungeDyke (Originally published in the Fall 2020 issue of Michigan Out-of-Doors)

Fall fly-fishing for northern pike is about chasing a moment. All of it – the equipment, the strategy, the effort – comes down to a glimpse of a pike underwater stalking the streamer, a brief pause, and the sudden, violent strike. Within that brief moment is all the adrenaline of the strip-set and the anticipation of wondering if the fish is on the line, followed by the elation of a heavy tug or the disappointment in a slack retrieve. Last fall I invited some friends from different conservation organizations in Michigan and Wisconsin up to my family’s Upper Peninsula lake cottage for a long weekend to chase that moment, along with Jordan Browne of Michigan Out-of-Doors TV to film it for a National Wildlife Federation film, Northwoods Unleaded. We spent three fun-filled days reeling in northern pike with nontoxic gear for both spinning and fly rods while the September leaves changed color overhead. Michigan anglers have long traveled to Canada for trophy northerns but there are ample opportunities to catch northern pike throughout Michigan. My grandpa and I used to catch them trolling with spoons on Lake Skegamog in the northern Lower Peninsula when I was younger, and my family has been catching northern pike at our cottage on Chaney Lake since my great-grandpa bought it in the late 1950’s. In fact, a postscript to the first entry in the cottage log notes that “Grandpa Bill caught a beautiful 24 1/2-in. northern.” Chaney Lake is a small 530-acre lake near the Ottawa National Forest in Gogebic County. Our dock points to the deepest depression in the lake, reaching about 20 feet deep, while the edges boast shallow weeds perfect for pike to ambush prey and a large shallow weed complex at one end for spawning. Chaney Lake is under special pike regulations allowing the take of up to five pike under 24 inches and one over, designed to increase the size of the fish in the lake and reduce the abundance of “hammer handles.” Similar regulations are being considered for additional lakes throughout Michigan by the DNR Fisheries Division. George Lindquist, past Michigan United Conservation Clubs president, caught a hammer handle off the dock as the first evening approached, as did Craig Challenor, president of the Wisconsin Wildlife Federation. With the bite on, we split up into two groups with the gear anglers on George’s 17-foot boat and the fly anglers with me in our little aluminum rowboat. George’s crew cast into the drop-off. We heard the shouts from George’s boat as Sarah Topp and Ryan Cavanaugh caught beautiful pike. Sarah is the former On The Ground coordinator for Michigan United Conservation Clubs and Ryan is the co-chair of the Michigan Chapter of Backcountry Hunters and Anglers. Sarah caught one over 24 inches and kept it to pair with the next day’s lunch of pasties from Randall’s Bakery in Wakefield. Marcia Brownlee, director of Artemis Sportswomen, and Aaron Kindle, director of sporting campaigns for the National Wildlife Federation, joined me in the rowboat with fly rods. We worked the weed edges extending out from shore. As Aaron rowed, I cast an articulated streamer with nonlead dumbbell eyes to the weed edge and stripped it back on my 8-wt rod. I watched a northern pike follow it a few feet below the surface and strike suddenly when I paused the retrieve. With a strip set, I had my first northern pike on the fly. It fought violently into Aaron’s net just as the sun was setting across the lake. It was only about 18-20 inches but I released it. Later in the weekend, l caught another small northern just off the shallow weeds on a Lefty’s Deceiver fly weighted with tungsten putty. Everyone on the trip ended up catching pike, but I was the only one to do so on a fly rod. As a novice pike fly angler, though, I wanted to know if this was just luck or if I was actually fishing the right spots with the right equipment and the right tactics for fall northern pike. “For lakes, I like to search on the edges of shallow flats where pike will ambush baitfish,” advised Kole Luetke, a fly-fishing guide for Superior Outfitters out of Marquette. “I also continue to fish the typically key structure that I fish thought the year, such as weed beds and deadfalls on the shore line. The key is to locate the baitfish, and in the later season warmer water temps. On rivers, I fish typical structures like deadfalls and slow backwater and sloughs.” Kole guides clients for multiple species across the Upper Peninsula, including northern pike and muskies. He uses somewhat similar tactics for both, though he uses relatively smaller flies for northern pike. “Oftentimes during the fall when I'm hunting bigger fish I will utilize the ‘L-turn’ or ‘figure 8’ like in musky fishing,” he said. “My retrieve speeds slow down when the water temps drop, and I like to utilize long pauses throughout the retrieve.” As with the ones I caught, northern pike will follow the fly – often all the way back to the boat – and strike during the pause. Rather than lifting the line for another cast, drawing a figure-8 with the fly with the rod tip down gives the pike more opportunity to strike. Kole uses larger flies than the smaller streamers I fished, though. “In the fall I like to increase the size of fly I use. Typically, I fish articulated flies anywhere from 8 to 12 inches. I don't often exceed the 12-inch mark for pike, but I will occasionally throw triple-articulated flies over 12 inches,” Kole said. “My preferred fly colors are fire tiger, brown and yellow, and white is killer in the tannic waters of the UP. In order to turn over large flies I use a shortened leader, 18 inches of 40-50lb Fluorocarbon connected to 18" of 40lb bite wire. This is similar to the leader I use for fall musky fishing.” With Kole’s advice, I’m looking forward to another trip up to the cottage this fall for pike fly fishing, but probably solo. I’ve tied larger articulated flies in the colors he suggested, bought a 9-wt Orvis Clearwater rod and a sinking line to better cast them, and rigged up some wire tippet leaders along with premade ones from Scientific Angler. I’ll target the same weed edges, structure and drop-offs, but I know it won’t be quite as fun without the whole crew there this time. That moment of anticipation between seeing the pike follow the streamer, pausing the retrieve, and the sudden burst of underwater violence will make it all worth it, though. Travelling to the far end of the Upper Peninsula isn’t necessary to find it, either. Wherever you are in Michigan, there’s a lake or a river nearby holding northern pike and endless opportunities to chase that moment. By Drew YoungeDyke This Michigan Outside column was originally published in the January 2020 issue of Woods'N'Water News. The cliché is that you can’t judge a book by its cover, but can you get to know a fisherman by his tackle box? The concept has been on my mind since I brought my great-grandpa’s tackle box home from my parents’ house a couple months ago on the way back from the Upper Peninsula cottage where it had rested since he died in 1981, the year after I was born. While I have a few pictures of him holding me as a baby, I never had the chance to fish with him. I hoped, though, that I could learn more about him as a fisherman by examining the contents of his tackle box. Some background on my great-grandpa helped get me started. His name was William Lantta, “Grandpa Bill,” and he lived in Ironwood, Michigan, as an electrician in and later underground foreman of the Geneva iron mine. He bought the family cottage on Chaney Lake – the one I write about so often lately – in 1959, but he also used to fish Island Lake in Wisconsin, where his siblings had a cottage. Chaney Lake has been a northern pike lake for as long as my family has been fishing it: the first cottage log entry is post scripted as “Grandpa Bill caught a beautiful 24 ½” northern.” A quick Google search for Island Lake tells me it holds muskies, northern pike, panfish, smallmouth bass, and walleyes. And family photos of him from the 1910’s and 1960’s are adorned with stringers of northerns. Grandpa Bill’s tackle box is green and metal with a leather-wrapped handle. It’s dinged and dented and well used, resembling the condition of the old aluminum rowboat at the cottage and the color of its oars. Even without knowing the specifics of the lures in his tackle box, a quick glance at the five and six-inch painted wood lures in the top tray tell you that it belonged to a mid-century pursuer of big toothy predator fish. The most distinctive lure is a six-inch wooden Mud Puppy made by the C.C. Roberts Bait Company. It was invented in 1920 by Constance Roberts of Mosinee, Wisconisin, and was a widely-used muskie lure in the mid-twentieth century. Its short revolving tail provided enticing action to muskies and northerns, and its glass eyes indicate it was made before WWII, when the glass eyes imported from Germany became unavailable, according to a detailed history of the lure written by Dan Basore in Midwest Outdoors. Another distinctive wooden lure in the box is a Heddon Basser, with “head-on Basser” scripted in a metal plate across the open smiling mouth that would provide a topwater splashing action for smallmouth or, more likely, hungry northerns. In place of the treble hook on its tail, though, a lead sinker was wired to the eyelet, maybe for use in jigging the last time it was fished. A five-inch jointed wooden minnow reminded me of the articulated streamer I used to catch my first northern with a fly rod earlier this fall. At first I thought it was a Creek Chub Pikey Minnow, but the hardware looked different. The metal lip and cup rig for the hook looked more like photos I’ve seen of old Isle Royale lures, which were made in Jackson, Michigan. The purpose would be the same: enticing northern pike to strike. Classic lures fill out the tackle box, including a wooden South Bend Bass Oreno, a Creek Chub mouse lure, and a Johnson’s Silver Minnow in its box which looks more like a 1930’s box than a mid-century one. There is also a weedless spinner, a fish-shaped painted metal Phleuger lure, and two spoons, one stamped as the “Spindare” from B & E Bait Co of St. Paul, Minnesota. Additional tackle includes a wire trolling leaders with flashers, cork and wood bobbers, sinkers, chicken bouillon cubes, treble hooks, swivels, a spool of 18-pound test “All Silk” casting line, and a spool of 15-lb. test “Best-O-Luck” braided nylon casting-trolling line from South Bend. He likely cast these from a South Bend No. 1000 Anti-Backlash Reel, as indicated by the empty box for just such a baitcasting reel. A1952 Michigan Legal Fish Rule from Merschel Hardware in East Tawas, Michigan, ensured the fish he kept were legal to keep. What does all this tell me about the fisherman who fished these lures, though? I already knew he fished for northern pike and musky, and the lures confirmed it. The bass plugs are also effective topwater lures for northern pike, but he might have also used them for smallmouth. He used both casting and trolling line, and had a metal trolling leader rigged with flashers, as well as a Heddon Basser rigged for jigging, so he probably used all three methods. And the fish rule tells me he made sure to follow the size limits set by the Michigan Conservation Commission, later the Natural Resources Commission. That’s just the fisherman he was on the surface, though. Below the surface, his tackle box tells me even more. It wasn’t filled with multitudes of lures and baits for any given situation; it had just a handful of well-worn classics that could have probably been found in the tackle boxes of most freshwater predator anglers of the region and time. And most of the lures ranged from the Depression through the 1950s. And yet, Grandpa Bill lived until 1981. So it suggests that he was a fisherman who took care of his equipment. He fished a handful of lures he trusted for decades, and the chipped paint and tooth marks indicate that they were well-used as he enjoyed the woods and waters of the western Upper Peninsula and northern Wisconsin on days off and later retirement from subsurface toil in the iron mine to provide for his family. There was one more object in the tackle box, though, from which no firm conclusions can be drawn. It’s a folded advertisement and order form for Flatfish lures from Helin Tackle Company of Detroit, Michigan. With no Flatfish in the tackle box, I’m left to wonder if he had a notion of ordering one but never did, or if it came with one that maybe broke off one day while reeling in a beautiful northern on Chaney Lake. Maybe one day when I jump in Chaney Lake after taking a sauna at the cottage I’ll find a long-lost Flatfish lure on the lake bed. Or maybe I never will and the purpose of that ad will always remain a mystery. The nature of my great-grandpa as a fisherman is just a little bit less of a mystery to me, though. Tackle boxes like his adorn shelves and back corners of garages and sheds throughout the upper Midwest, and lures like his fill pages of eBay auctions. My great-grandpa’s tackle box gave me just a little more insight into who he was as an angler and a man, though, and that’s much more valuable than what his lures could fetch in an online auction. Those lures are going to stay in that tackle box for future generations of my family to rediscover. POSTSCRIPT: I received an message from my mom's cousin Gretchen, who used to fish with him as a child and teenager, after she read the article. She wrote, "I recognized some of the baits, especially the yellow one (Mud Puppy). I remember the ones we (he) used most often were a red and white metal bait called a daredevil... We fished a lot with him. He was very quiet and would go out in ALL sorts of weather... sit for ever and ever. There was no joking around. He was very good at cleaning fish and did so on a narrow slab of wood on stick like legs on the hillside in front of the cottage. There were so many fish when we were young that he had made a homemade smoker (made from an old refrigerator and wood burning stove)... we had crappies for breakfast! Ina (his second wife) was a very good fish cook. I think he mostly smoked the northerns." That's sisu in so many ways. By Drew YoungeDyke This Michigan Outside column was originally published in the November 2019 issue of Woods'N'Water News. Water wolf, hammer handle, gator, snot rocket: northern pike go by many names in Michigan, often by bass anglers upset at their ruined baits. Esox lucius has a distinction no other fish can match, though: the only circumpolar freshwater fish in the world. These ambush hunters are the top predators in most of their waters, ranging across the lakes and rivers of the north with a rich history in both biology and mythology. And catching one on a fly has been an obsession of mine for the last year.

The obsession started last summer while trolling for walleye with Mike Avery and Tom Lounsbury on Saginaw Bay. I caught a 28-inch northern pike, and it awakened a long-dormant connection to the fish after over a decade of focusing mostly on trout when I fished. My grandpa and I used to troll for northern pike on Lake Skegamog, Elk Lake, and Torch Lake out when I was in college. We never caught many fish but those days with him during his last few years were priceless. Northern pike go back much further in my family history, too. The extended Finnish side of my family has a cottage on Chaney Lake in the far western Upper Peninsula. The first entry in the cottage log ends with the postscript, “Grandpa Bill caught a beautiful 24 ½” northern.” Chaney Lake is a small lake home to many northerns, if not big ones. Photos in the family albums show a succession of proud anglers holding northerns throughout the years. I thought of that one I caught with Mike as beautiful, too. The dark green body, the light spots giving it camouflage, and especially the intricate black swoops and patterns on its golden fins. They were as beautiful to me as the red spots on brown trout. The next day I went bowfishing with John Cleveland, a representative for Dardevle lures – the classic pike spoon - and he told me about fly fishing for northern pike up in Canada. I envisioned fly fishing for northerns out of the old aluminum rowboat on Chaney Lake and it made perfect sense. Like any new obsession, I started with the literature. The Michigan Department of Natural Resources released a Management Plan for Northern Pike in Michigan in 2016. “Habitat is a key factor in determining Northern Pike population dynamics in inland waters,” it notes. Northern pike spawn in shallow aquatic vegetation and flooded wetlands adjacent to water bodies, and their loss through shoreline development has reduced northern pike habitat, especially in southern Michigan. One of the DNR’s top goals for northern pike is to “protect, restore, and enhance habitat on Michigan waters,” noting that the loss of spawning habitat, especially through aquatic plant management, is “a major threat to the state’s Northern Pike fisheries.” A 1988 report for the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations gave a synopsis of all the biological data known about northern pike at the time. What I found most interesting was how they hunted. Using camouflage to blend into cover, often vegetation, northern pike first see the prey with one eye, then slowly turn their body to face it, then stealthily approach it until it’s just a couple inches away. Then it bends its body into an “S,” coiling like a spring, straightening into a strike, its mouth closed until the final instant, when it opens quickly. This creates a suction drawing the prey in, where the pike’s inwardly-inverted teeth make escape almost impossible. For 60 million years, this design has allowed northern pike to thrive throughout the northern freshwaters of the world. In Finland, northern pike are called hauki (which has become my favorite hashtag to follow on Instagram). Northern pike play a prominent role in ancient Finnish mythology, as preserved in the national epic poem The Kalevala. The hero of The Kalevala, Vainamoinen, slays “the mighty pike of Northland,” feeds everyone with it, and creates a magic harp from its jawbone. A prayer to the water-god Ahto asks him to “stir up all the reeds and sea-weeds, hither drive a school of gray-pike, drive them to our magic fish-net.” I wondered if my great-great-grandpa felt a connection to the Finland he emigrated from at age 17 catching pike in northern Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula where he lived to age 95. Pike fishing is still popular in Finland and other northern European countries. I found some YouTube videos from Finland-based Vision Flyfishing helpful in learning the basics of fly fishing for northern pike, along with the Orvis Guide to Fly Fishing Series episode on pike and muskie. The Orvis Fly Fishing Podcast with Tom Rosenbauer had some good pike-focused episodes, and talking with outdoor writer Tim Mead helped, too, who has fly fished for northern pike in the Upper Peninsula with a float tube. Over the spring and summer I geared up. I ordered an 8-wt Orvis Encounter fly rod and reel package and an assortment of large streamers and popping bugs. I ordered from Orvis to ensure that the weighted eyes and bead-heads in my flies were nontoxic: Chaney Lake supports a pair of loons, which can be poisoned when they ingest lead fishing weights lost or broken off. It also hosts bald eagles which fish its waters and can get lead poisoning from eating fish which have broken off line with lead weights attached. I also bought a used fishing float tube which I tried out on a few likely pike waters over the summer, without catching any. This would be harder than I thought. My friend Chris Engle took me to a favorite pike lake with his daughter and my dad. I didn’t catch any but his daughter, Paige, caught a dandy with a spinning outfit. I also fished sections of the Huron River near my home in Ann Arbor that I thought likely for northern pike, and had a couple strikes, but no catches. Finally, I got up to Chaney Lake in September, along with some friends from different conservation organizations for a weekend of hunting grouse and fishing for pike with non-lead ammo and tackle. Michigan United Conservation Clubs president George Lindquist brought his 17-foot fishing boat and we also had the cottage’s aluminum rowboat. George caught the first northern of the weekend off the dock in the early evening, and since they were biting we figured we should get out on the lake and catch them! George took a crew in his boat and I set out in the rowboat with my National Wildlife Federation colleagues Aaron Kindle and Marcia Brownlee, who manages Artemis Sportswomen. As Aaron rowed, I cast an articulated streamer with (non-lead) weighted eyes and stripped the line back. The northern stalked it, and I waited until it struck to strip-set the line, and it was on. Aaron netted it and I finally had my first northern pike on a fly! It wasn’t large – maybe 20 to 24 inches – and I released it without measuring. I caught another the next day after losing the articulated streamer and molding tungsten putty around the head of another streamer to give it the same effect as weighted eyes. By the end of the weekend, everyone caught at least one northern. Sarah Topp, AmeriCorps coordinator at Huron Pines in Gaylord, caught a keeper that we grilled for a delicious lunch snack the next day. And after a summer of not catching any, and on Chaney Lake, out of the aluminum rowboat - just as I had envisioned - I finally had the water wolf of the north at the end of my fly line. |

AUTHOR

Drew YoungeDyke is an award-winning freelance outdoor writer and a Director of Conservation Partnerships for the National Wildlife Federation, a board member of the Outdoor Writers Association of America, and a member of the Association of Great Lakes Outdoor Writers and the Michigan Outdoor Writers Association.

All posts at Michigan Outside are independent and do not necessarily reflect the views of NWF, Surfrider, OWAA, AGLOW, MOWA, the or any other entity. ARCHIVES

June 2022

SUBJECTS

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed