|

Originally published in the April 2022 issue of Woods-N-Water News

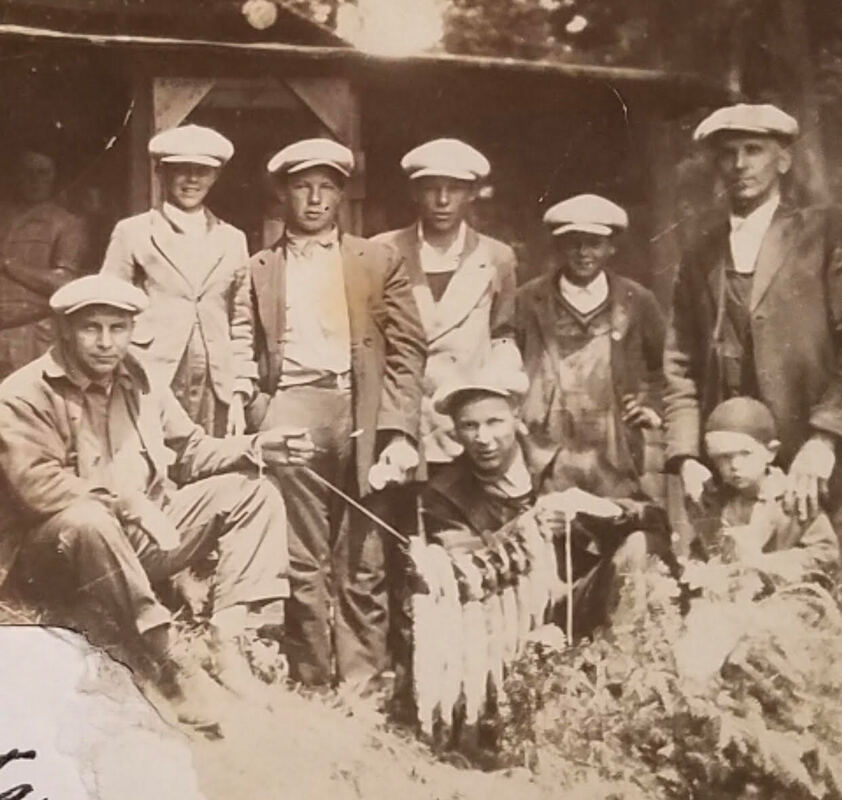

Drew YoungeDyke Spring blooms hope in the heart of every angler; no matter the past season’s frustrations, a new season of fishing arrives with warmer weather, ice out, post spawn and spawning fish, and optimism envisioned in every cast. Year round catch-and-release for many species has scarcely dimmed the traditions around the first day for keeper season for many species, even if we mostly catch-and-release, anyway. Michigan’s traditional trout opener on the last Saturday in April holds a rich history. Robert Traver (pen name of former Michigan Supreme Court Justice John D. Voelker and author of Anatomy of a Murder) wrote “Trout Madness,” a bible for any Michigan fly angler, which begins with the essay “First Day” recounting Traver’s opening day exploits chasing trout in the Upper Peninsula. “The day is invested with its own special magic, a magic that nothing can dispel,” Traver wrote. “It is the signal for the end of the long winter hibernation, the widening of prison doors, the symbol of one of nature’s greatest miracles, the annual unlocking of spring.” Traver’s trout opener journal entries from 1936 to 1952 are as memorable for stuck fish cars and frozen ponds as for trout, but much like the opening day of deer season, the traditions of deer camp often are more memorable than the empty buck poles. Jim Harrison - the late author, poet, and angler - grew up and lived in Michigan most of his life. In a 1971 article, “A Plaster Trout in Worm Heaven” – contained in his “Just Before Dark” collection of nonfiction - he describes why the trout opener doesn’t always produce the best trout fishing. “The first day always seems to involve resolute masochism; if it isn’t unbearably cold, then the combination of rain and warmth manages to provide maximal breeding conditions for mosquitoes, and they cloud and swarm around your head, crawl up your sleeves and down your neck, despite the most potent and modern chemicals.” A couple years ago I joined some friends for a Trout Camp up in the Pigeon River Country for opening day. We camped out the night before with snow falling and frigid temperatures, warmed up by beaver stew and moonshine. The next morning, I realized I’d left my reel at home in Ann Arbor – four hours away – so I joined the Headwaters Chapter of Trout Unlimited’ s annual Pancake Breakfast at the forest headquarters without so much as wetting a line. The Pigeon River Country Discovery Center at the headquarters contains an exhibit about Ernest Hemingway, who spent his summers in northern Michigan as a youth and often fly fished in the Pigeon River Country and the Upper Peninsula. The exhibit contained an excerpt from a letter he’d written inviting friends to a similar fish camp in the Pigeon River Country a hundred years earlier, which he referred to as the Pine Barrens. “Picture us on the Barrens, beside the river with a camp fire and the tent and a good meal in our bellies smoking a pill with a good bottle of grog.” That’s the spirit of the trout opener whether any fish are caught or not. Spring fishing openers are about the optimism of looking forward to warmer summer days on the water. Tom McGuane – perhaps the finest fishing writer ever – also grew up in Michigan and used to fish in the Pigeon River Country, too. In “Small Streams in Michigan” - contained in his collection of nonfiction fishing writing, “The Longest Silence” - he describes fishing the Pigeon, Black, and Sturgeon Rivers: “I’d pick a stretch of the Pigeon or the Black for early fishing, wade the oxbow between the railroad bridges on the Sturgeon in the afternoon. Then, in the evening, I’d head for a wooden bridge over the Sturgeon near Wolverine.” I’m mostly a failed trout angler. After fifteen years of catching more tree branches than trout on a fly, I was almost ready to give up on serious fly fishing until John Cleveland told me about fly fishing for northern pike during a Michigan Outdoor Writers Association conference in 2018. That lit something in me, and since then I’ve been obsessed with it, gearing up with heavy weight fly rods and lines to cast giant bucktail streamers. It led me into fly tying, then into more purposeful and successful fly fishing for the other species that inhabit pike waters like bluegill, crappie, perch, and bass. The obsession has become so complete that I don’t even bow hunt anymore because it cuts into my fall pike fishing time. The Lower Peninsula pike opener is also the last Saturday in April, like the trout opener, but I have the Upper Peninsula pike opener of May 15 circled on my calendar. My family has a cottage in Gogebic County on a lake dominated by northern pike, where I caught my first two pike on the fly in 2019. My great grandpa, who bought the old logging camp bunkhouse and deer camp shack to convert into a family cottage in the 1950s, used to host his family fish camp there and before that on a little lake across the border in Wisconsin containing musky and northern pike. A fish camp on May 15 would provide perfect symmetry to the annual deer camp firearm opener on November 15, being perfectly six months apart, dividing the year in two. I hosted some friends for pike camp at the cottage in the September before the pandemic struck and it felt like I was on to something. Reviving that fish camp tradition – more than a century after he started it – would be like coming out of that long winter hibernation that Traver wrote about. Maybe I’m just looking for that magic that nothing can dispel. A magic that would allow me to fish with my ancestors, in whatever weather comes, and maybe share a bottle of grog like Hemingway, even if I’m the only one on the lake. By Drew YoungeDyke (Originally published in the May 2021 issue of Woods-n-Waters News)

On vacation on Kauai a few years ago, I took a surf lesson on Hanalei Bay from Titus Kinemaka’s Hawaiian School of Surfing. As a souvenir, I bought a ballcap from the surf shop with his name and the words “Kai Kane” on it, meaning “waterman.” I’ve seen the term waterman used often since then as I’ve read more about surfing, referring to someone who makes a living from the water like lifeguards, guides, and surfing instructors, and is well-rounded in water sports like surfing, stand-up paddling, paddling kayaks and canoes, fishing, diving, sailing, and swimming. I’ve wondered often how the concept of a waterman – or waterwoman – would translate to Michigan’s Great Lakes and inland waters. Waterman seems to be a term that is more than the sum of its definitions. It’s a term of reverence. It’s used for people like Duke Kahanamoku – the “Father of Surfing” – who won several Olympic gold medals for the United States and set world records in swimming in the early Twentieth Century, popularized surfing around the world, and once rescued 24 people from an overturned boat off the California coast. Or Eddie Aikau, a big-wave surfer and the first lifeguard at Hawaii’s famed Waimea Bay, who rescued hundreds as a lifeguard and died himself while paddling his surfboard for help to rescue his crew of an overturned replica of an ancient catamaran in 1978. More recently, the term is used for people like Kai Lenny, a champion surfer and kiteboarder from Hawaii who once kiteboarded across Lake Michigan. As best I can tell, waterman is an aspirational concept that you can’t really just call yourself. It’s not like saying “I hunt and fish, so I’m an outdoorsman.” It seems to be more like when all the other hunters and anglers say, “we all hunt and fish, but old so-and-so is a true outdoorsman.” It’s not just reserved for men, either – it’s one of those terms that isn’t gender-specific in common usage even though it literally is written as such. A waterman seems to be someone inextricably connected with the water. With 3,288 miles of Great Lakes coastline, over 51,000 river miles, and over 11,000 inland lakes, I know there are some men and women in Michigan for whom waterman might be an apt descriptor. I asked a few folks who I know and think embody that term what it means to them in a Michigan context. Brian Kozminski is a fly-fishing guide and the owner of True North Trout in Boyne City, a sales rep for Temple Fork Outfitters, and a river rafting guide for Jordan Valley Outfitters: “I am not a waterman in the aspect of being a lifeguard or surfer, unless you dig deeper into the definition of life guard - I protect and look out for the well-being of my inland lakes and rivers, the voice or the guardian of these sacred places that carry so much vitality. The rhythms of the waves or the flow of a river are a part of me, they are my serenity and it is near the water that I feel connected to life and being alive. So I guess in that sense, I am a surfer, with my children as we seek out adventure along the Great Lakes in a canoe or SUP, or in a stream where we turn over a rock to inspect the macroinvertebrate life that resides in these hallowed spaces. These rivers and lakes give me purpose and fulfill my soul - thereby, I am a waterman.” Brian’s answer gave me a lot to think about. There’s an inescapable element of conservation in it. I’ve fished with Brian and, drifting down the Manistee River, he knew every eddy, every current, every cut bank. He understands the water and what’s happening in it. And he lives it, from recreation to conservation. He’s active in several conservation organizations like Backcountry Hunters & Anglers, Trout Unlimited, the Great Lakes Business Network, and the National Wildlife Federation. In addition to guiding anglers from his drift boat, I’ve seen him fishing from a stand-up paddleboard and you can watch him drifting a motorboat backwards down a river on Season 2 of MeatEater’s Das Boat series. Another person I thought of was Tom Werkman, owner and guide at Werkman Outfitters on the Grand River. I asked him what it would mean to be a waterman in Michigan. “It means I intimately have a connection to the river on which I guide, the Grand River. It means I have a responsibility, as a guide, to educate my clients on the history of the Grand, that it’s one of ruin to recovery. It means, I need to get my clients on fish so they can make a connection to the Grand. If all of this happens, it means, for me, that I have done my job of showing my clients that the Grand River is a viable urban fishing corridor worthy of protection.” Tom, too, has an unmistakable conservation message in his definition: conserving his waters, being connected to them, and connecting others to them. I’ve also fished with Tom, and like Brian, his connection to and knowledge of his waters and their history is paramount. Tom is also a member of the Great Lakes Business Network, several conservation organizations, and has used his platform to speak up for Michigan’s public lands and against dredging the Grand River. And in addition to guiding anglers from a drift boat, he also surfs and competes in triathlons. What does it mean to be a waterman in Michigan? While I can ponder it, it’s not up to me to define it. From two people I respect who make a living on our waters by connecting other people to them and spending their free time conserving them, though, I suspect it involves a genuine visceral connection to the water, making a living or spending a great deal of time on the water, understanding it deeply, connecting other people to it, advocating and volunteering for its conservation, and being well-rounded in water-based sports and modes of transportation. I think there’s an element of water safety to it, too. The Great Lakes can be deadly. 30 years later, I still remember the fear of being caught in a Lake Superior rip current swimming when I was 11 or 12. I’m learning more about that and Great Lakes currents while learning about freshwater surfing. I think about that when I read about the increase in Great Lakes drownings the past few years, often people swimming out too far or being swept off piers. The great Hawaiian watermen were revered not just for their skill in water sports, but for their heroism in saving others and their deep understanding of how to safely move in the water to be able to make those rescues. The point of this exercise is not to label people, though, as waterman or not; that’s not my call to make. It’s to think about qualities that all of us who spend time around and on the Great Lakes and Michigan’s inland lakes and rivers can strive to emulate. If we fish a river, we can learn a little more about its history and ecology. If we participate in water sports, we can learn more about water safety, both for ourselves and to help others. We can learn and improve our skills at new water sports and modes of transportation so that we can be out there more often in more diverse conditions. If we spend time on the Great Lakes, we can learn more about its cycles, currents, aquatic life, and waves. We can leverage our own existing connections to the water to introduce new people to them. And we can all put more of our time, effort, and attention into conserving and protecting our waters. By Drew YoungeDyke (Originally published in the March 2021 issue of Woods-N-Water News)

If you’ve tried to buy new outdoor gear in the past year, you’ve likely experienced frustration at the lack of stock. As the pandemic has required people to keep social distance, a boom in outdoor recreation participation has occurred packing trails and campgrounds and emptying inventories of everything from kayaks to cross-country skis. You don’t need the newest gear to have fun outside, though. As I’ve seen the “out of stock” notifications on the websites for my favorite manufacturers, though, I’ve also realized how much of my outdoor recreation is reliant on old gear that still works. For those who are looking to use their socially distant time to try new outdoor sports, this also means that you don’t have to let a lack of new inventory hold you back. Gear found at second-hand stores, garage sales, or internet resale marketplaces can get you outdoors enjoying Michigan’s woods, waters, and wildlife, if it’s still in working condition. Some of my favorite gear to still use was either handed down, found at a garage sale, or purchased decades ago. For instance, I’ve spent all winter cross-country skiing almost every weekend and most lunch breaks (when there was enough snow) on Karhu Classic Touring skis that I’ve had since college and that my dad first purchased in the 1980’s. As waxless skis, they require little upkeep – until this winter I had last waxed them at least a decade ago – but they still give me a good glide and decent traction uphill. I even use them to get my two-year-old son out in the snow by either towing his sled or carrying him in a backpack carrier while I ski. I’ve been looking at upgrading to new skis but the ones I want are out of stock, even online. Thankfully my old Karhu’s continue to work well even after three decades. Garage sales can be great places to find working outdoor gear. My parents enjoy shopping at garage and estate sales in the summer, so I have them keep an eye out for outdoor gear for me. A few years ago, my dad found a pair of Yukon Charlie Backcountry snowshoes with a broken decking, but with a little duct tape they’ve carried me on multiple winter backpacking trips over the years. My only current hunting bow also came from a garage sale. Shortly after I bought my first compound bow a decade ago (at a Wyoming pawn shop) I expressed an interest to learn to shoot a traditional bow. My dad called me from a garage sale a few years ago and said that there was a recurve bow for sale for $10. I asked if there was any apparent limb twist or cracking, and he said he didn’t think so. I figured for that price, though, it was worth the shot. It turned out to be a Shakespeare Super Necadah, made in Kalamazoo in the late 60’s or early 70’s, and it shoots great. My most prized outdoor gear was handed down from my grandpa, who instilled my passion for fishing and conservation, and mentored me along with my dad in hunting. One of these items is a Marlin Model 1892 lever-action .22 rifle. This century-old rifle is my favorite squirrel gun, loaded with copper .22LR ammunition. When he was still alive and I was in college, we fished together often on summer weekends in his boat on Lake Skegamog, Elk Lake, Torch Lake, and other inland lakes in the northwest Lower Peninsula for northern pike and smallmouth bass. Along with sage advice and lifetime memories, he gave me his Fenwick Voyageur 4-piece fiberglass spinning rod. To this day, even 16 years after he died, it’s the only spinning rod I use. I mostly fly fish now, and while I’ve bought some newer Orvis rods for bass and pike, the Cortland rod and reel package I got for Christmas in college is still what I use for trout and panfish. This past year, with more time to fish and less opportunity to do much else, I caught more panfish than ever mostly on my 17-year-old 5-wt Cortland starter package (with newer Scientific Anglers line and mostly flies I tied myself). And no fish have ever meant more to me than the bluegills and pumpkinseeds I caught on that rod with my son in a backpack on Father’s Day last summer. And while new kayaks were flying off of outdoor retailer shelves last summer, there’s no watercraft I’d rather fish out of than the aluminum rowboat at my family’s Upper Peninsula lake cottage. It’s older than me (and I just turned 41!) but it floats and catches fish. I repainted the oars last summer and my dad and brother replaced the rotten transom a few years ago. Replacing the cracked wood bench seats is next on my list. Watching the MeatEater series “Das Boat” on YouTube – much of it filmed in Michigan last summer – has given me an endless list of future ideas for it, as well. And as the tagline for that series says, “Whatever floats.” I’m as much of a gear junkie as anyone, and I appreciate the technological advances in materials and construction that outdoor gear and clothing manufacturers are continually putting into their products. And I certainly buy my fair share of new outdoor gear when my budget allows, but I also rely on gear that has withstood decades of use and still gets me outdoors. Some of it has sentimental value, but some of it was just a good deal. Whether you’re looking to learn a new outdoor sport or whether finances are just tough, as they are for many right now, don’t let a lack of funds keep you from enjoying outdoor recreation. A new fishing rod may be nice, but an old one can still cast a lure. New skis may go faster, but old ones will still glide. New snowshoes may not require duct tape, but old ones will still keep you from post-holing. And while every fly angler may dream of new drift boats or every bass angler may dream of new sparkle boats, the only real requirement for catching fish is that it floats and you do the rest. And no matter what gear you see others using out in the woods, on the water, or on Instagram, the only gear you need is the gear that gets you out there. Whether you’re using old gear to learn a new skill, because it’s the gear you could afford, because it’s the gear you trust, or because it’s the gear your grandpa used, you belong out there. Get whatever gear you can get your hands on, get outside, and have some fun. Whatever floats. By Drew YoungeDyke (Originally published in the Fall 2020 issue of Michigan Out-of-Doors)

Fall fly-fishing for northern pike is about chasing a moment. All of it – the equipment, the strategy, the effort – comes down to a glimpse of a pike underwater stalking the streamer, a brief pause, and the sudden, violent strike. Within that brief moment is all the adrenaline of the strip-set and the anticipation of wondering if the fish is on the line, followed by the elation of a heavy tug or the disappointment in a slack retrieve. Last fall I invited some friends from different conservation organizations in Michigan and Wisconsin up to my family’s Upper Peninsula lake cottage for a long weekend to chase that moment, along with Jordan Browne of Michigan Out-of-Doors TV to film it for a National Wildlife Federation film, Northwoods Unleaded. We spent three fun-filled days reeling in northern pike with nontoxic gear for both spinning and fly rods while the September leaves changed color overhead. Michigan anglers have long traveled to Canada for trophy northerns but there are ample opportunities to catch northern pike throughout Michigan. My grandpa and I used to catch them trolling with spoons on Lake Skegamog in the northern Lower Peninsula when I was younger, and my family has been catching northern pike at our cottage on Chaney Lake since my great-grandpa bought it in the late 1950’s. In fact, a postscript to the first entry in the cottage log notes that “Grandpa Bill caught a beautiful 24 1/2-in. northern.” Chaney Lake is a small 530-acre lake near the Ottawa National Forest in Gogebic County. Our dock points to the deepest depression in the lake, reaching about 20 feet deep, while the edges boast shallow weeds perfect for pike to ambush prey and a large shallow weed complex at one end for spawning. Chaney Lake is under special pike regulations allowing the take of up to five pike under 24 inches and one over, designed to increase the size of the fish in the lake and reduce the abundance of “hammer handles.” Similar regulations are being considered for additional lakes throughout Michigan by the DNR Fisheries Division. George Lindquist, past Michigan United Conservation Clubs president, caught a hammer handle off the dock as the first evening approached, as did Craig Challenor, president of the Wisconsin Wildlife Federation. With the bite on, we split up into two groups with the gear anglers on George’s 17-foot boat and the fly anglers with me in our little aluminum rowboat. George’s crew cast into the drop-off. We heard the shouts from George’s boat as Sarah Topp and Ryan Cavanaugh caught beautiful pike. Sarah is the former On The Ground coordinator for Michigan United Conservation Clubs and Ryan is the co-chair of the Michigan Chapter of Backcountry Hunters and Anglers. Sarah caught one over 24 inches and kept it to pair with the next day’s lunch of pasties from Randall’s Bakery in Wakefield. Marcia Brownlee, director of Artemis Sportswomen, and Aaron Kindle, director of sporting campaigns for the National Wildlife Federation, joined me in the rowboat with fly rods. We worked the weed edges extending out from shore. As Aaron rowed, I cast an articulated streamer with nonlead dumbbell eyes to the weed edge and stripped it back on my 8-wt rod. I watched a northern pike follow it a few feet below the surface and strike suddenly when I paused the retrieve. With a strip set, I had my first northern pike on the fly. It fought violently into Aaron’s net just as the sun was setting across the lake. It was only about 18-20 inches but I released it. Later in the weekend, l caught another small northern just off the shallow weeds on a Lefty’s Deceiver fly weighted with tungsten putty. Everyone on the trip ended up catching pike, but I was the only one to do so on a fly rod. As a novice pike fly angler, though, I wanted to know if this was just luck or if I was actually fishing the right spots with the right equipment and the right tactics for fall northern pike. “For lakes, I like to search on the edges of shallow flats where pike will ambush baitfish,” advised Kole Luetke, a fly-fishing guide for Superior Outfitters out of Marquette. “I also continue to fish the typically key structure that I fish thought the year, such as weed beds and deadfalls on the shore line. The key is to locate the baitfish, and in the later season warmer water temps. On rivers, I fish typical structures like deadfalls and slow backwater and sloughs.” Kole guides clients for multiple species across the Upper Peninsula, including northern pike and muskies. He uses somewhat similar tactics for both, though he uses relatively smaller flies for northern pike. “Oftentimes during the fall when I'm hunting bigger fish I will utilize the ‘L-turn’ or ‘figure 8’ like in musky fishing,” he said. “My retrieve speeds slow down when the water temps drop, and I like to utilize long pauses throughout the retrieve.” As with the ones I caught, northern pike will follow the fly – often all the way back to the boat – and strike during the pause. Rather than lifting the line for another cast, drawing a figure-8 with the fly with the rod tip down gives the pike more opportunity to strike. Kole uses larger flies than the smaller streamers I fished, though. “In the fall I like to increase the size of fly I use. Typically, I fish articulated flies anywhere from 8 to 12 inches. I don't often exceed the 12-inch mark for pike, but I will occasionally throw triple-articulated flies over 12 inches,” Kole said. “My preferred fly colors are fire tiger, brown and yellow, and white is killer in the tannic waters of the UP. In order to turn over large flies I use a shortened leader, 18 inches of 40-50lb Fluorocarbon connected to 18" of 40lb bite wire. This is similar to the leader I use for fall musky fishing.” With Kole’s advice, I’m looking forward to another trip up to the cottage this fall for pike fly fishing, but probably solo. I’ve tied larger articulated flies in the colors he suggested, bought a 9-wt Orvis Clearwater rod and a sinking line to better cast them, and rigged up some wire tippet leaders along with premade ones from Scientific Angler. I’ll target the same weed edges, structure and drop-offs, but I know it won’t be quite as fun without the whole crew there this time. That moment of anticipation between seeing the pike follow the streamer, pausing the retrieve, and the sudden burst of underwater violence will make it all worth it, though. Travelling to the far end of the Upper Peninsula isn’t necessary to find it, either. Wherever you are in Michigan, there’s a lake or a river nearby holding northern pike and endless opportunities to chase that moment. By Drew YoungeDyke (Originally published in the August 2020 issue of Woods-n-Waters News)

It’s fortunate that some of the simplest fish to catch are also some of the most fun and accessible: panfish on public land lakes. Public land lakes are open to everyone and fish like bluegills, pumpkinseeds, and crappies are fun for everyone from the beginner to the expert to catch due to their abundance, appetite, fight, and mild flavor when kept and cooked. And as more people are venturing outdoors to paddle and fish to maintain social distance, Congress is advancing bipartisan legislation to provide greater public access to fishable waters to catch them. Earlier this summer, I packed a deflated fishing float tube in a backpack and hiked just under a mile from a parking area along a trail to a lake within the Bald Mountain Recreation Area in northern Oakland County. The trail runs along a grassy water control structure for the little warmwater lake where I’ve had success in past years fly fishing for bluegills and largemouth bass from shore. With a float tube and a couple boxes of flies I tied this year, though, I wanted to fish the whole lake and catch some largemouth bass or northern pike. While inflating my float tube and assembling my fly rod, though, I could see bluegills and pumpkinseeds on their gravel beds near shore where I planned to launch, so I tied on a little foam hopper I tied up this spring. I cast it just past the bluegills and stripped it lightly over top of them so the foam lip could pop the water like a little bass popper. Curious bluegills swam up to it and nibbled until one took a confident bite and I set the hook. Immediately the bluegill exploded, darting every which way underwater trying to free the hook. I played it lightly since I’d only brought my 9-weight rod for casting larger bass bugs and pike streamers, but it was still fun even on that heavy line. The six-inch bluegill was my first on a fly I’d tied, to which I quickly added six- and seven-inch pumpkinseeds and a crappie. Content with my shoreline panfish catch, I launched my float tube and fished the weed edges, structure, and shaded pockets along the shoreline. A green bass popper was too big for the dozens of panfish that nibbled at it, but I finally connected with a topwater largemouth bass that fought with everything it had, burying itself in weeds before I scooped it out with my net. What fun! I passed a pair of anglers in a green canoe on the way back to the launch and we chatted briefly at a distance. Mike and Megan Schumer, father and daughter, lived nearby and showed me the full catch of crappies they’d already reeled in from the lake for a panfish dinner. That’s what it’s all about, I thought. I returned for a few hours for the next three days and caught 29 total fish, mostly bluegills and pumpkinseeds, a few largemouth bass, and a pair of crappies, including one which took the 2/0 red and white Clouser Minnow I tied for northern pike! One of those days I kept five bluegills and pumpkinseeds over six inches, filleted them and pan-fried them for a fish taco lunch the next day, all courtesy of our public lands. The Bald Mountain Recreation Area is state-owned public land acquired in large part by a $197,000 grant from the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) approved in 1966 just after the fund was created by Congress in 1965. The LWCF operates on the same principle as the Michigan Natural Resources Trust Fund, created a decade later. It uses the royalties from offshore gas and oil development – not taxes - to acquire and develop outdoor recreation opportunities for everything from public land, trails, and boat launches to baseball fields and park pavilions. Last year, the LWCF was permanently authorized through the John D. Dingell Conservation, Management and Recreation Act, a welcome example of bipartisanship for our public lands. However, only twice in its 55-year history has Congress ever actually appropriated the full amount authorized to the Land and Water Conservation Fund. Which means that every dollar less than that full amount has been money intended for the LWCF but siphoned to other uses. That could finally change thanks bipartisan legislation moving through Congress as of this writing. The Great American Outdoors Act (GAOA) will permanently fund the Land and Water Conservation Fund to its full authorized amount of $900 million each year, as well as fund a backlog of maintenance projects at federal national parks and other public lands. The National Wildlife Federation and the Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation worked to ensure that federal public lands open to hunting like Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Fish and Wildlife, and U.S. Forest Service lands were included. The GAOA recently passed the U.S. Senate, considered its biggest hurdle, and as of this writing is expected to be soon considered by the U.S. House of Representatives. In Michigan, though, one of the biggest beneficiaries of Land and Water Conservation Fund grants has been anglers, as much of it has been used to acquire and develop boat launches and the acquisition of public lands containing fishable water like Bald Mountain Recreation Area (which also received LWCF funding to develop its shooting range). The passage of the Great American Outdoors Act will ensure that even more investments in public water access and public lands can be made in more places, providing future generations with places to fish. I returned down that same trail to that same public land lake on Father’s Day. Instead of a float tube, though, I had my 16-month-old son Noah in a backpack carrier and my 5-weight fly rod in hand. Along the way, I passed or was passed by hikers, mountain bikers, and trail runners, all of us keeping a safe distance. And while I may have tried not to notice it before, they appeared to represent multiple different races and ethnicities. We smiled and greeted each other. They wished me Happy Father’s Day, and I thanked them and wished the same, and I hoped that I was as welcoming to everyone else on the trail as they were to me. Everyone belongs outdoors, and our public lands belong to all of us. With my son on my back, I tied the same foam popper to my fly line and cast it into the near shore waters, in the pockets between the lily pads and weeds where bluegills and pumpkinseeds swam. It took a few casts until I felt that tug, the furious rush, and I played the six-inch bluegill back to shore, the first that Noah and I caught together. I held it up for him to see and he looked at it curiously, not sure what to make of it. That’s alright, I thought. He’ll be more excited in a couple years when he feels that tug for himself. We caught a few more on foam hoppers, Chernobyl ants, and a foam bass popper I tried to catch a largemouth with, but which enthused a pumpkinseed more. While we fished, people passing on the trail nearby asked questions about what I was fishing for, and with what, and I answered. Maybe they were part of the new influx of people discovering or re-discovering the outdoors as a way to social distance during this COVID-19 pandemic. Maybe now they’ll try out a worm on a hook on the old spinning rod or baitcasting reel in the garage they never used or they’ll buy a new one, and now they know a spot. I’m happy to share, because these panfish and public lands are for all. This will always be the place where my son and I caught our first fish together. Maybe we’ll come back more as he grows up and we’ll fish it often like Mike and Megan Schumer do, enjoying parent-child bonding time long after he’s a child. Maybe one of those hikers will pick up a fishing rod and catch her first fish in that same spot and feel that tug that hooks her for life. After all, isn’t that what it’s all about? |

AUTHOR

Drew YoungeDyke is an award-winning freelance outdoor writer and a Director of Conservation Partnerships for the National Wildlife Federation, a board member of the Outdoor Writers Association of America, and a member of the Association of Great Lakes Outdoor Writers and the Michigan Outdoor Writers Association.

All posts at Michigan Outside are independent and do not necessarily reflect the views of NWF, Surfrider, OWAA, AGLOW, MOWA, the or any other entity. ARCHIVES

June 2022

SUBJECTS

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed